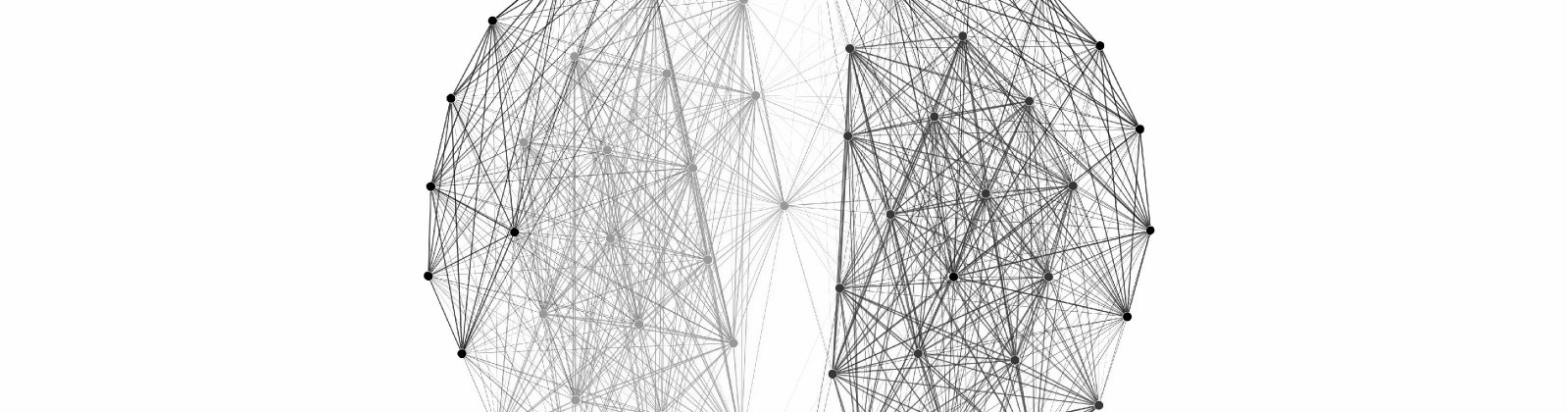

This Christmas break I decided to try to get the cover of my new article (Update: looks like they chose another very cool cover). In essence, that work shows that the thalamic reticular nucleus on each side of the brain shows functional connectivity with the visual nuclei on both side of the brain. My goal was to try to express this through a simple and beautiful graph (final image above).

To do this, I needed three types of files:

- Functional MRI data (in my case, the mean run of a participant looking at my stimulus).

- Anatomical masks (these were drawn on the thalamic nuclei using proton density weighted images, but could be any atlas).

- Statistical masks (regions of the brain that survive some statistical threshold, i.e., q[FDR] < 0.05).

The goal is to find, within each anatomical region, x arbitrary time series, and correlate them. To get started, I define some imports and useful functions.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import nibabel as nib

import networkx as nx

def calculate_normalizer(ts):

minimum = np.min(ts)

maximum = np.max(ts)

divisor = np.max(np.array(np.abs(minimum), np.abs(maximum)))

return divisorThis min-max normalizer is useful when visualizing time series with largely different magnitudes. Since correlations are insensitive to these sorts of scaling operations, it won’t affect our image.

def load_nifti(filename):

"""

Loads a nifti file, returns the data matrix reshaped to 2D and it's original

dimensions.

"""

data = nib.load(filename)

# retrieve the dimensions

dims = data.shape

nvox = dims[0]*dims[1]*dims[2]

ntrs = dims[3]

# retrieve the matrix

data = data.get_data()

data = np.reshape(data, (nvox, ntrs))

return dataThis loads our NIFTI data using Nibabel and reshapes it to a voxels x timepoint 2D matrix, which I find much easier to work with. In this case, our masks will become vectors of integers and we will use them to filter out the columns of the fMRI data that we are interested in looking at.

# mask ROIs: 1 = rlgn, 2 = llgn, 3 = rvtrn, 4 = lvtrn, 5 = rdtrn, 6 = ldtrn

rois = [1, 2, 4]

n_samps = 20

outnames = ['01_rlgn-ts', '02_llgn-ts', '03_lvtrn-ts']Here I’m just defining some options for later on: let’s look at the right & left LGN as well as the left ventral TRN. These are stored as integer values [1, 2, 4] in the anatomical mask. From each of these regions of interest (ROIs), let’s grab 20 arbitrary voxels. Since we are going to save the traces, let’s also make a list of output names here.

Next, we’re going to load in the data, find statistically relevant regions within each target ROI, and plot them as a stack of subplots. This is so we can extract the traces in Inkscape / Illustrator later. Finally, for each ROI, take the 20 traces and stack them onto master out_ts matrix that we will use to draw our correlation matrix later.

# load timeseries data, anatomical ROIs, and statmask from retino (q[FDR]=0.05)

mean_run = load_nifti('mean_functional_run.nii.gz')

mask = load_nifti('mask_anatomy.nii.gz')

stat = load_nifti('mask_statistics.nii.gz')

# plot x time series from each ROI

for i, val in enumerate(rois):

# find the values within each ROI that are statistically significant

idx = np.intersect1d(np.where(mask == val)[0], np.where(stat > 0)[0])

plt.figure(num=None, figsize=(2, 8))

# take the first x, arbitrary

for n in range(n_samps):

# calculate normalizer (min/max)

divisor = calculate_normalizer(mean_run[idx[n], :])

# generate each subplot

plt.subplot(n_samps, 1, n)

plt.plot(mean_run[idx[n], :] / divisor, linewidth=2, color='black')

plt.ylim(-2, 2)

plt.axis('off')

plt.suptitle(str(val))

plt.savefig(outnames[i] + '.svg')

plt.close()

# if this is the first one, init the out_ts matrix

if i == 0:

out_ts = mean_run[idx[:n_samps], :]

# otherwise, stack them

else:

out_ts = np.vstack((out_ts, mean_run[idx[:n_samps], :]))Let’s look at the data we’ve extracted so far:

Next we correlate these time series to create a weighted graph of the data.

# generate correlation matrix

cmat = np.corrcoef(out_ts)

# plot full graph and thresholded graph

plt.imshow(cmat, vmin=-1, vmax=1, cmap=plt.cm.RdBu_r, interpolation='nearest')

plt.axis('off')

plt.savefig('04_full-mat.svg')

plt.close()

cmat[cmat <= 0] = 0

plt.imshow(cmat, vmin=-1, vmax=1, cmap=plt.cm.RdBu_r, interpolation='nearest')

plt.axis('off')

plt.savefig('04_pos-mat.svg')I turned off most of the matplotlib label features so I could add in a few of my own in Inkscape. This is what the data looks like:

We are removing negative correlations because there is some debate in the literature about how to best interpret these relationships, and they aren’t particularly relevant to the questions we’re asking.

Finally, we export the matrix using networkx to a format Gephi understands. Gefx is a XLM-based format that is relatively nice to read. We’re also going to number the nodes by ROI (1 = right LGN, 2 = left LGN, 3 = left TRN). This will help us visualize the relationships between these regions in topographic space.

# turn thresholded matrix into a networkx graph object

g = nx.Graph(cmat)

# number the nodes by ROI

for n in g.nodes():

if n < n_samps:

g.node[n]['label'] = 1

elif n >= n_samps and n < n_samps*2:

g.node[n]['label'] = 2

else:

g.node[n]['label'] = 3

nx.write_gexf(g, '05_pos-mat.gexf')We can import this file into Gephi (version 0.8.2). At first things won’t look very informative at all:

We can use the ‘partition’ feature on the left edge of the overview screen to allow us to color-code our graph according to the labels we assigned earlier:

And finally, we can select from one of the many available layouts to arrange the nodes. These algorithms aren’t paying attention to the labels of the nodes, but rather the distribution of correlations contained within the edges of the graph. This is a ‘topographic’ space, turning anatomical (or ‘real world’) distance into statistical distance can give you amazing insight into your data. I chose the Fruchterman Reingold algorithm to group correlated nodes together in a way that I thought would be pleasing for a magazine cover (note that I also scaled up the edge width to 3 and turned off the ‘curved edges’ option):

The force atlas 1 layout tells a similar story in a clear, more ‘scientific’ visualization:

With a little bit of tweaking, these graphs can be beautiful communication tools.

For a script with the above code as well as the output images along the way, check out the cover section of my repo dedicated to this publication.